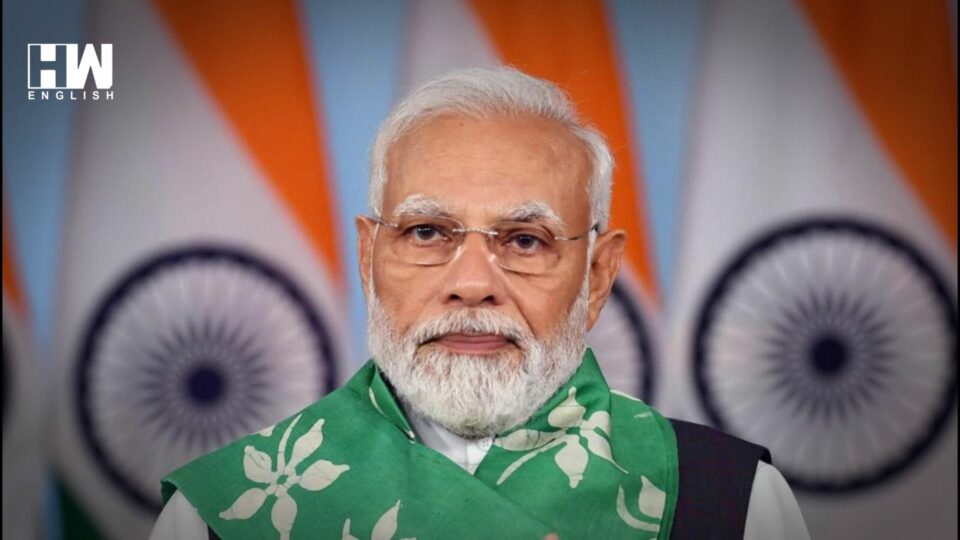

Many people expect Prime Minister Narendra Modi to win a third term, and most predictions focus on how much the BJP will win by. However, the explanations for this are usually very polarized.

One side praises Modi for his global vision, strong leadership, and rapid progress. The other side claims that institutions have been manipulated, the opposition has been targeted, and a compliant media is stirring up communal tensions and exaggerating the government’s achievements.

What often gets lost in these heated debates is an unbiased look at the actual facts and data on the ground.

Over the past two months, this six-part series aimed to do just that by examining some of Modi’s key welfare schemes. The first article looked at the PM’s ‘housing for all’ scheme, the second at health insurance, the third at financial aid to farmers, the fourth at the rural roads program, the fifth at the clean drinking water initiative, and the last at the free foodgrain program.

Where’s the Money Going?

The welfare system in India has changed significantly under PM Modi. During his 2014 election campaign, he promised “Maximum Governance, Minimum Government” and criticized the rural employment guarantee scheme from the Manmohan government, suggesting he might reduce government welfare programs.

However, under Modi, the government has launched new benefits and expanded existing schemes, often with great publicity. These include gas cylinders under Ujjwala, toilets under Swachh Bharat, water connections under Jal Jeevan, houses under PM Awas, cash transfers under PM-KISAN, food grains under PM Gareeb Kalyan Yojana, and health insurance under PM Jan Arogya Yojana, either free or at subsidized costs.

But where has the money come from, especially since the economy hasn’t performed better in the last 10 years compared to the previous decade? The annual GDP growth during the 10-year NDA period is 4.86 percent, while it was 6.14 percent during the UPA years.

Budget documents show that in 2013, the UPA government spent almost 27 per cent of its annual budget on subsidies (food, fertilizer, and fuel), rural employment, mid-day meals, child development services, rural water delivery, and other welfare schemes. Despite adding many new schemes, the NDA government has not exceeded this 27 percent mark, except for a surge in food subsidy in 2020-21 due to Covid relief.

This is partly due to a reduction in the subsidy bill, mainly from cutting the fuel subsidy. The government has also prioritized its signature schemes over other initiatives. For example, funding for education has consistently decreased over the last decade, while health funding hasn’t changed much compared to 2013.

The Modi model of welfare delivery is more pragmatic and attuned to the daily struggles of the poor. It may also be more effective from a public perception and electoral perspective.

However, claiming sole credit for every government initiative ignores the significant role of state governments. India’s federal nature determines how schemes are implemented. While the Centre announces initiatives and provides funds, many welfare schemes target areas that are the responsibility of state governments. The execution of these schemes varies significantly from state to state, based on regional priorities. For example, Bihar has nearly 100 per cent penetration of the Jal Jeevan Mission, while Kerala struggles to reach 50 per cent, challenging common perceptions about both states.

While political will sets government priorities, but the role of bureaucrats and technocrats is crucial in the detailed execution of government functions. Many schemes are informed by previous committee reports, which serve as valuable knowledge repositories. Despite being seen as procedural, these reports ensure continuity in government policies and practices, even when political parties change. For example, the Aadhaar framework started under the UPA but is now associated with the NDA. This continuity amidst political change is a positive sign for a mature democracy.

While the NDA has improved welfare delivery, experts and Parliamentary Standing Committees stress the need for third-party inspections and social audits. Without these independent ground reports, government dashboard data always comes with an asterisk.

Building assets and maintaining them are two different things. The government excels at building but struggles with upkeep, such as maintaining roads or drinking water infrastructure. This makes social audits to assess ongoing scheme performance even more crucial.

Coverage is another area needing improvement.

Most welfare schemes have coverage gaps due to two systemic issues:

First, coverage targets are based on the 2011 Census. Since then, India’s population has grown by nearly 150 million, and the rural/urban distribution has changed. These changes are not reflected in scheme targets, leaving many beneficiaries unaccounted for.

Second, the issue of the ‘missing middle’ is highlighted in the context of PMJAY. As Niti Aayog noted, the lower-middle and middle-middle classes could afford many services with some subsidy help but are often overlooked in policy. Including this segment could also boost aggregate demand in the economy.

They say politics is the art of the possible, which also extends to governance.

Examples include:

- Helping those with land and capital build houses under PM Awas while ignoring the worse-off urban homeless.

- Targeting in-patient care through PMJAY when out-patient care forms 40 to 80 per cent of household healthcare costs.

- Focusing on landed farmers through PM-KISAN while excluding landless farmers.

- Relying heavily on groundwater for water provision despite the risk of slippage.

These examples do not indicate malfeasance but show that what gets done is often what is easiest to do.

But Credit Where It’s Due

Women’s empowerment is a key theme across many consumables offered under this “New Welfarism.”

LPG cylinders eliminate the need to forage for cooking fuel and prevent the inhalation of cooking fire pollutants. Household taps reduce the burden of fetching water. These tasks generally fall to women, who disproportionately benefit from these initiatives. Toilets also provide freedom and dignity to women and health benefits to both genders. In a patriarchal society like India, efforts that empower women should be acknowledged and applauded. Political gains from improving the lives of half the electorate are well deserved.

Finally, as PM-KISAN shows, cash transfers have become a staple in Indian policy.

The electorate has consistently supported such transfers, and with the DBT framework, policy elites now deploy them on a large scale across parties. Whether these transfers compensate for state failure, a sensible hybrid of redistribution and market forces, or an abject withdrawal from providing public goods and services will be a crucial debate in the coming years.

As an independent media platform, we do not take advertisements from governments and corporate houses. It is you, our readers, who have supported us on our journey to do honest and unbiased journalism. Please contribute, so that we can continue to do the same in future.