Greater protection is needed for civil society representatives who are increasingly being targeted in repressive and life-threatening environments, UN and regional human rights experts said in a joint declaration published on Friday.

They urged governments to uphold their international obligations and ease access to protection measures for civil society actors fleeing violence, including recognition of refugee status and expedited emergency visas.

Desperate need of refuge

“Around the world, courageous individuals, and their organizations at the frontlines of the struggle for human rights are in desperate need of safe refuge and urgent life-saving humanitarian assistance yet face vast barriers to protection,” said Clément N. Voule, UN Special Rapporteur on the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and of association.

The independent expert issued the declaration alongside counterparts from Africa, the Americas and Europe.

In it, they deplored attacks against civil society actors, including killings and extrajudicial executions, enforced disappearance, persecution, hostage takings, arbitrary arrests, and sexual and other gender-based violence.

Their declaration also includes recommendations to enhance international efforts to both advocate for open civic space and support those under threat.

“As many States join this week’s Summit for Democracy to address the deepening trends in democratic regression and rising authoritarianism, there is an opportunity to move from rhetoric into action,” said Mr. Voule referring to the two-day meeting hosted by United States President Joseph Biden.

The Summit for Democracy ended on Friday, Human Rights Day.

UN Special Rapporteurs like Mr. Voule serve in their individual capacity and are not UN staff neither are they paid by the Organization.

They receive their mandates from the UN Human Rights Council, which is based in Geneva.

Freedoms, not just about words: Bachelet

Marking Human Rights Day in Geneva, UN human rights chief Michelle Bachelet held a live question-and-answer session on social media channels, to speak about the importance of reducing inequalities and advancing human rights – the twin themes of this year’s celebration.

Here’s a selection of questions she was asked, and the High Commissioner’s candid answers, on everything from mandatory COVID-19 vaccination to how everyone can get involved in pushing for a fairer and more sustainable rights-based future for all:

Question: How can you, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, fight against impunity and hold perpetrators of rights violations accountable?

Michelle Bachelet: It is the State’s obligation to hold those responsible [for human rights violations] accountable. Of course, we know many States don’t. The international community can also act. We assist Member States to develop their capability and help them in that process.

In case a Member State is not willing to hold anyone accountable, the international community can do that through special commissions of inquiry, monitor situations and publish findings in violations. We can also give such information to international courts, like the International Criminal Court or to national tribunals.

The Office of the High Commissioner is always following situations. There are a lot of mechanisms that can ensure that perpetrators can be held accountable.

Question: How is the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights working to protect the rights of ordinary people?

Michelle Bachelet: Human rights are about ordinary people – what happens to each individual in the workplace, school, street or community. We ensure ordinary people have the rights they deserve… access to education, access to a job, access to social benefits when in need, that children have access to play and enjoy a safe environment.

We work on all of that daily. Like Eleanor Roosevelt said, human rights are not an abstract concept, they are about what happens in the daily life of people. To ensure human rights, we must ensure that adequate laws and policies are in place. We also need to change the social, economic and cultural aspects if they are not allowing human rights to be protected and promoted.

Question: How can we make sure human rights are not only about words?

Michelle Bachelet: Human rights are not just words that can be read in a document; they are about being able to vote, being able to speak freely, being able to be critical without reprisals, to ensure journalists have freedom of press to inform people, to ensure people can access medical attention and go to school.

I understand the frustration of some people who see their leaders speak about human rights, but what is happening in their country is very different. Words matter; they are the first step to acknowledge that there is a violation of human rights, or that human rights are still not well protected.

To speak about gender equality, it means you have a goal to get to, even if you are not there yet. For example, we have not yet reached all the Sustainable Development Goals, but they give a guidance or roadmap to Member States to do what needs to be done. So that rights are not just words, people must be aware of their rights and demand them. That is why education in human rights is so important.

Question: Can we make vaccines mandatory?

Michelle Bachelet: I know this is very controversial. On one hand, vaccines need to be a universal public good so everyone can have access to them and they are affordable.

We see the terrible issue of inequity on vaccines. Rich countries have access to vaccines and up to 65 per cent of their populations are vaccinated, while African countries have only vaccinated two per cent.

As long as there are people who are not vaccinated, we will continue to have new variants and the pandemic will never end. On the other hand, people, because of fake information or lack of information, believe that vaccines can cause consequences, and that is not true. For people who want to be vaccinated but do not have access, this could be a sort of discrimination.

Question: Will there be a future where education is equally accessible across the world?

Michelle Bachelet: Education is a right that permits you to exercise other human rights. With COVID-19, 1.6 billion learners are out of school, and 11 million girls might not return to school. Education is key and essential. We all need to push to ensure education is available and accessible for everyone.

I see education as a vaccine, a vaccine to fight female genital mutilation, child pregnancy, child marriage, even a vaccine to try to prevent HIV/AIDS. Education is essential and we will be pushing strongly to ensure it is a right that should be respected now and forever.

Question: How much space have you created for more women and girls after you? And when you look back, will you be proud of the spaces you have created?

Michelle Bachelet: I have been lucky: I was the first Minister of Health in my country, the first Minister of Defence in my country and the fifth in the world, the first President of my country, re-elected twice, and the first Executive Director of UN Women.

Having been the first, I understand that I should push for other women and girls to have opportunities to thrive and to be protected. We need to do more and ensure women and girls are supported by their communities and the international community.

Defenders of women’s rights and environmental human rights defenders must really feel they are not alone and that they can continue to work strongly. It is a difficult struggle and women face a lot of prejudice and push back. But it is worth it.

Question: According to the 2021 report on plastic and human rights, the plastic crisis affects a broad range of rights, including equality and non-discrimination. How can we mainstream equality in the negotiation and provision of a potential treaty on plastic pollution?

Michelle Bachelet: It is not only the plastic crisis affecting human rights; a lot of other issues affect the environment: climate change, pollution, and biodiversity loss. We must deal with that.

In the Sahel countries, a very dry region of the world, you see all kinds of situations, conflicts between communities, farmers and herders, and they fight because of the lack of adequate land or sufficient water and they start killing each other because of that.

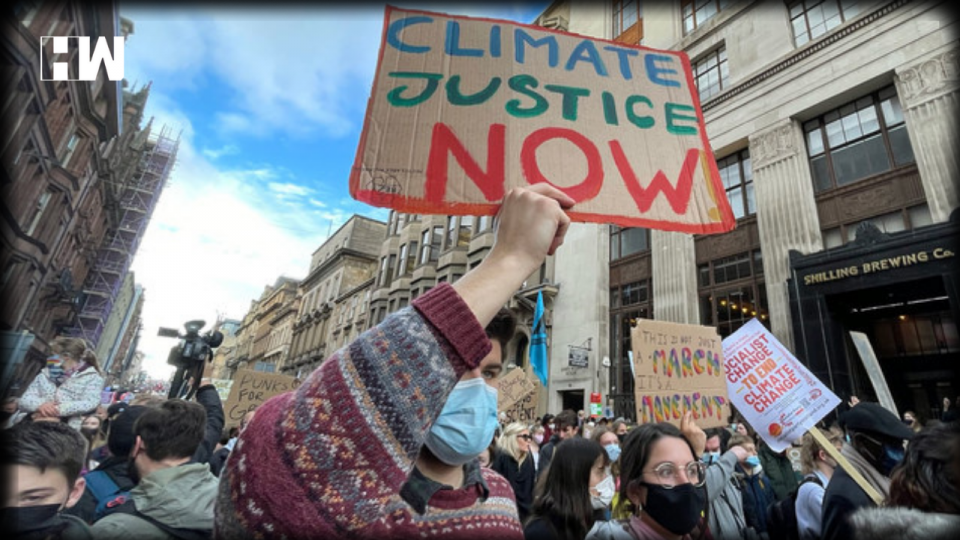

We have also seen an increase of drought and of flooding, causing internal displacement and migration. Many people do not understand the linkages between climate change and human rights. It is very important that people, especially young people, continue mobilising and calling on Member States to do the right thing, to ensure they work on climate change.

Question: How can people collaborate with the United Nations and work on human rights, including women and children?

Michelle Bachelet: First, you can do it in your community, you don’t need to do it with the United Nations. If you are a girl, you can start at school, talking about the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, on Human Rights Day or on any other day of the year.

You can also organize to work with others in the community to respect women’s rights and speak against domestic violence affecting women. There are also United Nations country teams, and girls can think of activities that can involve the United Nations at the country level. Girls can also participate in digital events.

Human Rights Day, commemorated on 10 December, celebrates the day the United Nations General Assembly adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948.

As an independent media platform, we do not take advertisements from governments and corporate houses. It is you, our readers, who have supported us on our journey to do honest and unbiased journalism. Please contribute, so that we can continue to do the same in future.