After the victory in WW II, allied countries convened a military trial to try the leaders of the Empire of Japan for joint conspiracy to start and wage war.

On April 26, 1946, after the victory of allied forces in the Second World War, the allied countries convened a military trial to try the leaders of the Empire of Japan for joint conspiracy to start and wage war. This trial held in Tokyo is referred as The International Military Tribunal for the Far East (IMTFE). It is widely known as Tokyo Trial, especially after the Netflix miniseries on the trial came out in 2016.

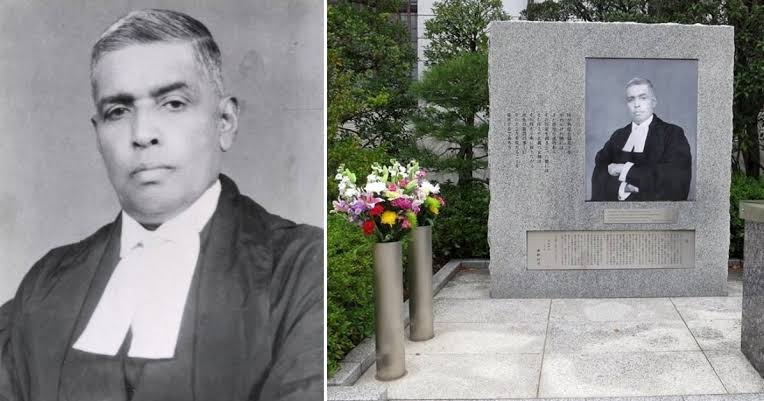

For this Tokyo Trial, allied countries had nominated 10 judges on the tribunal from the US, Canada, Britain, France, the Netherlands, Australia, New Zealand, the Soviet Union, China and the Philippines. However, in a fascinating series of events, Justice Radhabinod Pal of Calcutta High Court in India was inducted on the Tribunal. Allied countries included an Indian judge on the tribunal when India’s fight for freedom against British colonialism was reaching towards its culmination. According to National World War II Museum’s website, Justice Pal joined after protests from India about the lack of diversity on the Tribunal.

Who was Justice Pal?

Apart from being appointed as one of three Asian judges on the Tokyo Trial tribunal, Justice Radhabinod Pal was also an Indian jurist who was a member of the United Nations’ International Law Commission from 1952 to 1966.

Born in 1886 in Bengal Presidency (now Bangladesh) of British India, Justice Pal studied law from Presidency college in Calcutta.

It was not clear why the British and American authorities selected Judge Pal, who had served in Calcutta’s high court and strongly sympathized with the anticolonial struggle in India. As an Asian nationalist, he saw things very differently from the other judges.

The judgement

After the war, conventional war crimes by the Japanese, categorized as Class B and Class C, were handled in local trials throughout Asia. Twenty-five top leaders were charged with Class A crimes — of waging aggressive wars and committing crimes against peace and humanity, categories created by the Allies after the war — and tried in Tokyo by justices from 11 countries.

Over the final judgement, there could hardly have been any doubt in anyone’s mind what the judgement of the tribunal would be. The war was over, the Allies had won, and history would be written by the winners. Historian John Dower, talking of the trial, said that it was undeniable fact that the “trial was fundamentally a white man’s tribunal”.

The court found all the 25 defendants guilty. Seven were sentenced to death, 16 to life imprisonment, and two were sentenced to 20 years and seven years in prison, respectively.

Justice Pal, who was initially even accommodated at a hotel in Tokyo that was inferior to the one in which the other judges were staying, refused to be the token Indian on the bench and wrote a 1,235-page dissenting judgement.

Dissenting voice

Blatantly blunt in his observations, Justice Pal wrote that the tribunal was a “sham employment of legal process for the satisfaction of a thirst for revenge”. He said it is “failure of the tribunal to provide anything other than the opportunity for the victors to retaliate”. He concluded: “I would hold that every one of the accused must be found not guilty of every one of the charges in the indictment and should be acquitted on all those charges.”

Justice Pal argued that in colonizing parts of Asia, Japan had merely aped the Western powers. He had, in the beginning of trial, had made clear that he was not in favour of trying the accused under charges of crimes against peace and humanity. Even in his dissenting judgement, Justice Pal rejected the charges of crimes against peace and humanity as ex post facto laws. In a sharp question, he asked had the defendants committed any greater crimes against humanity than the US had done in Hiroshima and Nagasaki?

The National World War II Museum states the reasoning behind Justice Pal’s argument. “In his dissent, Pal advanced a historical perspective that integrated Japanese actions in Asia and the Pacific within the broader story of British, French, and Dutch colonialism. Japanese policy could not be separated, he contended, from that story of oppression, exploitation, and humiliation of Asian-Pacific people. Indian troops had been called on to fight for Britain continents away from their homes. Pal certainly spoke for many when he addressed Imperial Japan’s moves as responses to Western dominance. He completely rejected the prosecution’s fundamental claim of a conspiracy within the Japanese ruling class to wage war,” the Museum’s site said.

Still Revered In Japan

A monument of Justice Pal has been erected at the Yasukuni Shrine, the memorial to Japan’s war dead and a rallying point for Japanese nationalists. Many of postwar Japan’s nationalist leaders and thinkers have long upheld Judge Pal as a hero, seizing on his dissenting opinion at the Tokyo trials to argue that Japan did not wage a war of aggression in Asia but one of self-defense and liberation.

In 1966, Pal was awarded the Order of the Sacred Treasure First Class by the emperor of Japan, one of the country’s highest honours.

In 2007, on a visit to India, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzō Abe paid tribute to Pal, who died in 1967, in an address to Parliament. He then went to Kolkata to meet Pal’s son.

“Justice Pal is highly respected even today by many Japanese for the noble spirit of courage he exhibited during the International Military Tribunal for the Far East,” Mr. Abe told the Indian Parliament.

Objectivity of Justice Pal

Japanese historians and nationalists, in recent years, have used sections of Justice Pal’s judgement to bolster their argument that the Japanese were not aggressors or invaders in World War II. However, he would not have been pleased with it.

Justice Pal had not supported Japan in their war crimes. Instead, he argued that Japan could not and should not be singled out for its imperialist lust. In fact, in a speech he delivered at Hiroshima in 1952 (he had been invited by the Japanese government), he said: “If Japan wishes to possess military power again, that would be a defilement against the souls of the victims we have here in Hiroshima.”

Iconic personality

When Justice Pal joined the tribunal in 1946, India was still fighting for freedom. Until two years later when the trial concluded, India had achieved its independence and had been partitioned in two countries. Justice Pal was in Tokyo when all of this happened. His own village from Bengal Presidency would got to East Pakistan. It must have been difficult for him to be away from his homeland in such tumultuous circumstances. Moreover, when he delivered his dissenting judgment, he was aware that he was representing Independent India now, and his decision will hold immense importance for the future of his country.

There must have been immense pressure on Justice Pal from other white judges to toe the line. Living in an alien country for over two year, Justice Pal stuck to what he believed was true, right and just.

In his judgement, he wrote:

“I doubt not that the need of the world is the formation of an international community under the reign of law, or correctly, the formation of a world community under the reign of law, in which nationality or race should find no place.”

As an independent media platform, we do not take advertisements from governments and corporate houses. It is you, our readers, who have supported us on our journey to do honest and unbiased journalism. Please contribute, so that we can continue to do the same in future.